Guest post by Brooke Adams, Conservation Technician, Preservation and Conservation, University of Michigan Library

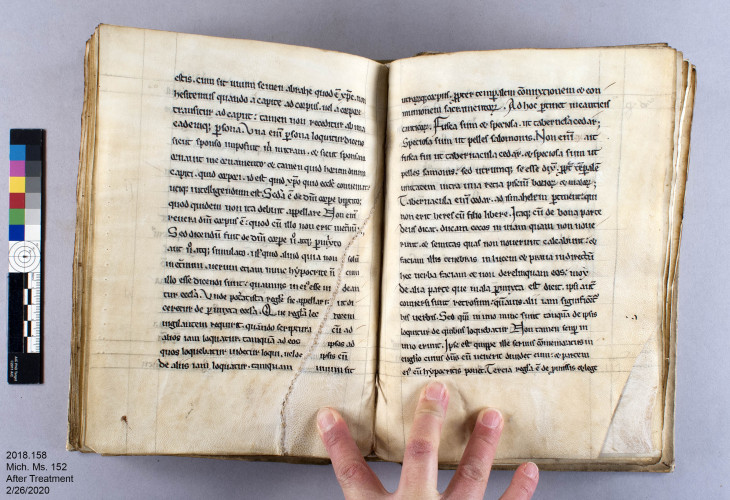

There are many beautiful and fascinating medieval and Renaissance manuscripts that can be viewed in the reading room of the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC). Out of the hundreds of manuscripts found at U-M, copied in many languages and representing various cultural traditions, including those of western Europe, Byzantium, and Islam, I will be focusing on Mich. Ms. 152, an extraordinary twelfth-century manuscript containing St. Augustine's De doctrina christiana. Copied on vellum (calf skin) in the twelfth century, it was re-bound with vellum over thick paper boards at the end of the fifteenth or beginning of the sixteenth century.

In 2016, shortly after I was hired as a Conservation Technician in the Department of Preservation & Conservation, Mich. Ms. 152 came to the lab with a batch of books that needed new protective housings. It was one of the first manuscripts I had the pleasure of touching and studying up close.

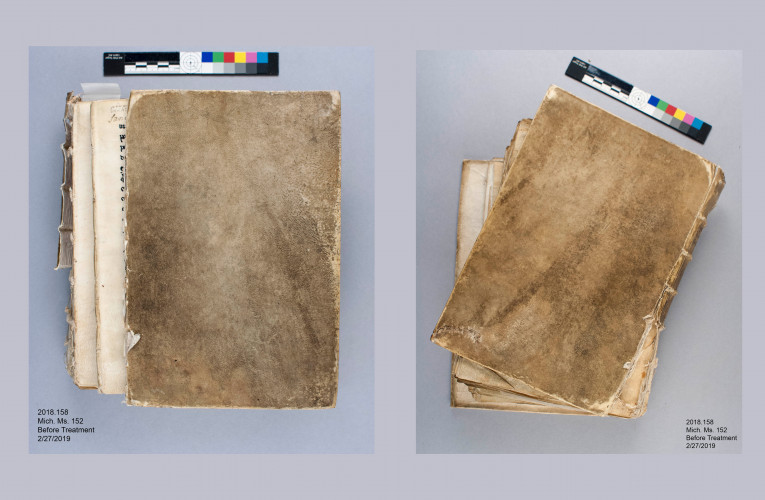

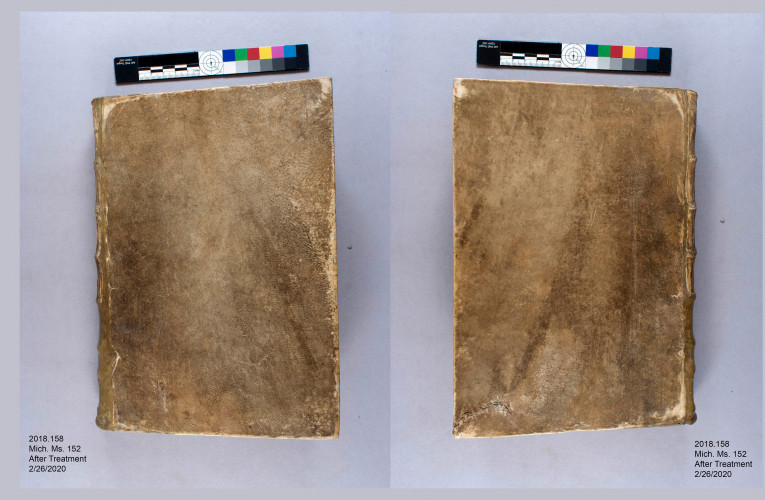

Mich. Ms. 152, upper and lower covers, before treatment

The effects of time on this manuscript are mesmerizing. The vellum covering the boards and spine has discolored with the accumulated dirt and environmental pollutants of past ages. Enticing old mends on the back cover and throughout the textblock are witnesses of the prudent frugality of the craftsmen from centuries past.

Mich. Ms. 152, old sewn mend in page tear

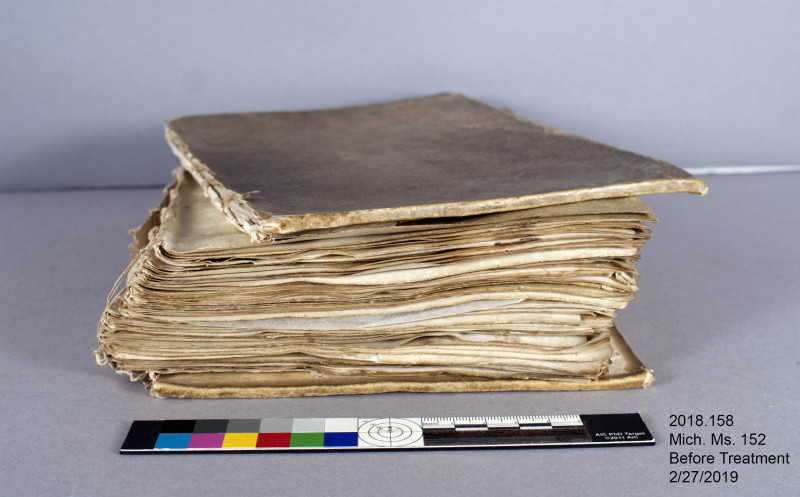

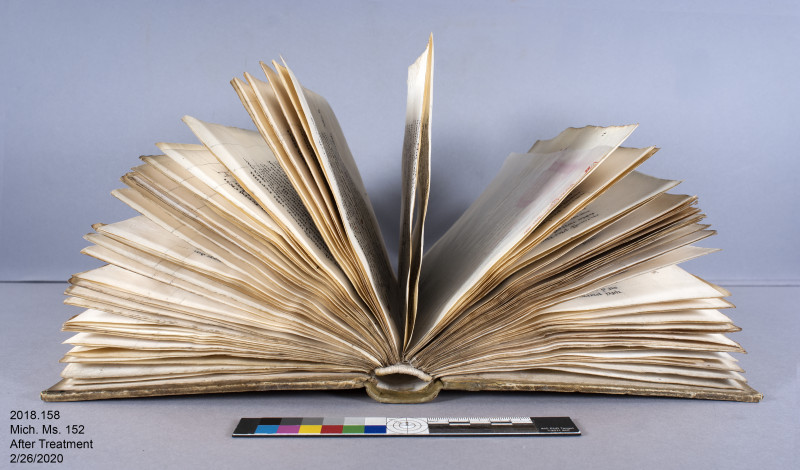

The size of this manuscript is average, at 10 inches tall, 6.5 inches wide, and 2 inches thick – but its thickness seems much more substantial when the book is in front of you. The covers are warped and the vellum pages are thick and cockled, causing the book to fan open, revealing its contents.

Mich. Ms. 152, lower edge, before treatment

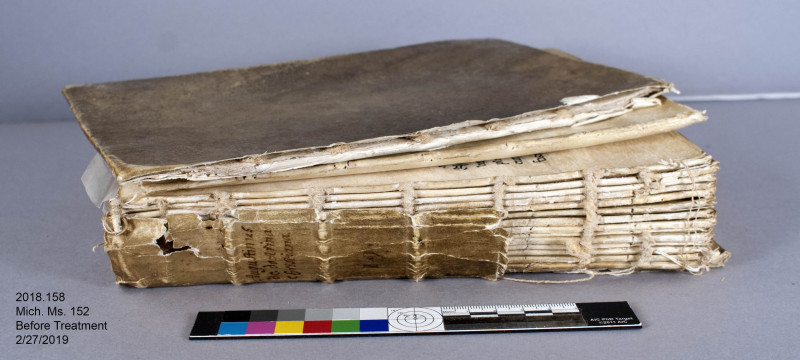

Mich. Ms. 152 came across my bench a second time in 2019 – this time for treatment. I was excited to not only get to work on this book directly, but to have the opportunity to perform a treatment I had never done before. The spine needed to be repaired using a technique known in conservation as a re-back. A re-back done on books with raised cords, such as the sewing supports on Mich. Ms. 152, is more complex than doing so on a book with a smooth spine, such as those with recessed or no sewing supports. Therefore, I followed a technique developed by the British book conservator Andrew Honey, that conservators call a “Honey Hollow.”

Mich. Ms. 152, damaged spine, before treatment

The Honey Hollow utilizes the technique of papier-mâché, making a mold of a book’s spine and its raised cords. This molded paper spine-former makes space for the raised cords and creates a support that protects the fragile original vellum spine from tension when the book is opened. Instructions were followed from Andrew Honey’s article, “The conservation of Annotationes in Libro Evangeliorum using a natural hollow over a moulded Japanese paper spine-former,” published in The Paper Conservator, Vol. 27, 2003.

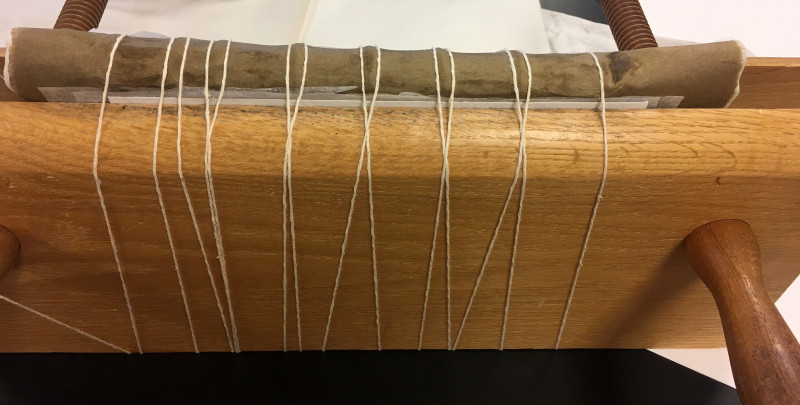

Because the original sewing was broken and damaged, the textblock was first completely dis-bound and resewn on raised cords with a similar profile to the original supports. The vellum along the joint edges of the covers was lifted and the covers were reattached to the resewn textblock using the ends of the sewing support cords as a point of attachment.

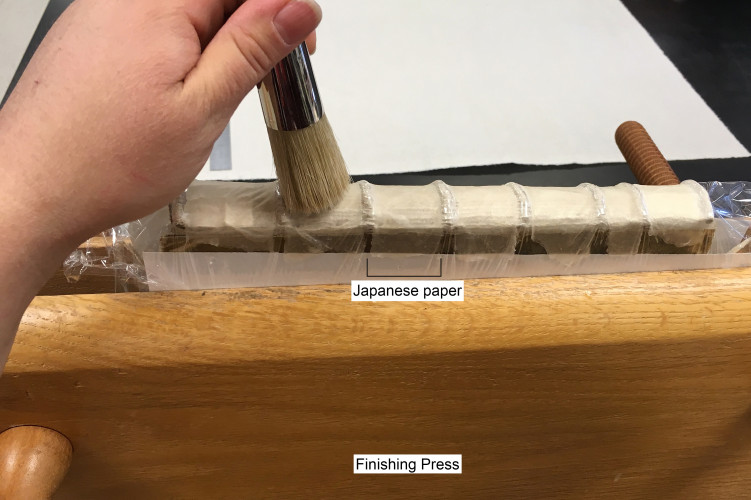

The spine was then lined with a thin Japanese paper called Sekishu, and new endbands were sewn off the book and adhered to the spine of the textblock at the head and tail. The first Japanese paper lining adds stability to the textblock and sewing, and acts as a protective layer between the original spine and the new repair materials. One goal in book conservation is to make repairs reversible so they can be removed if needed for future study or improvement. The next step was creating the molded paper spine-former, which was made using five layers of Sekishu Japanese paper adhered with wheat starch paste. Plastic wrap was used to separate the spine-former from the spine of the textblock.

Layers of paste and Japanese paper were used to create the molded spine-former

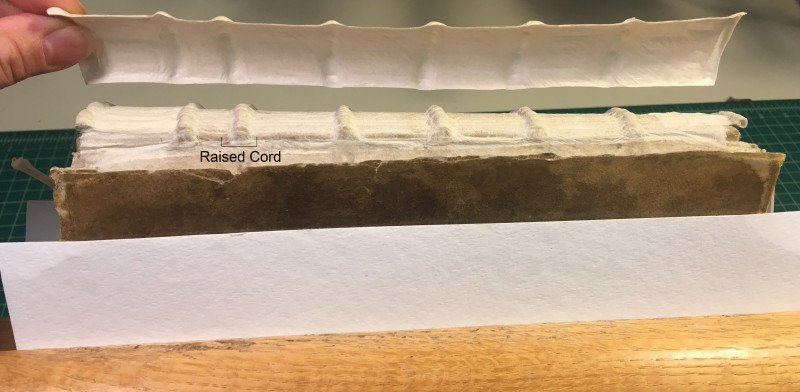

The molded spine-former, held over the spine of the textblock

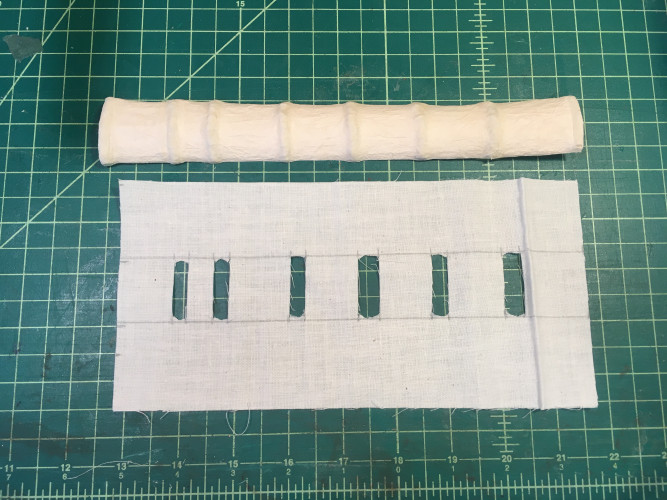

Once the spine-former was complete a piece of slotted cotton muslin was then adhered over the molded paper spine-former to hold it in place and provide more support along the joints. The slots in the lining ensure that the definition of the raised cords is not affected. The molded paper spine-former itself is not adhered to the spine of the textblock, which leaves a hollow space when the book is opened.

Slotted cotton muslin lining to go over the molded spine-former, holding it in place

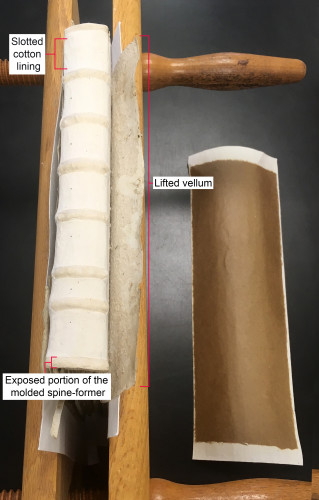

A Teflon folder is used to massage the adhesive-coated cotton lining over the molded spine-former and onto the boards, beneath the lifted vellum.

A Teflon folder is used to massage the adhesive-coated cotton lining over the molded spine-former

A piece of colored Moriki Japanese paper lined with cotton muslin is applied as the outermost layer of the re-back. The Moriki layer is adhered to the exposed portion of the molded spine-former, the slotted cotton lining, as well as overlapping onto the boards beneath the lifted vellum, along the joints.

Moriki layer to be adhered as the final layer of the re-back

String is used to help adhere and define the raised cords as the adhesive dries

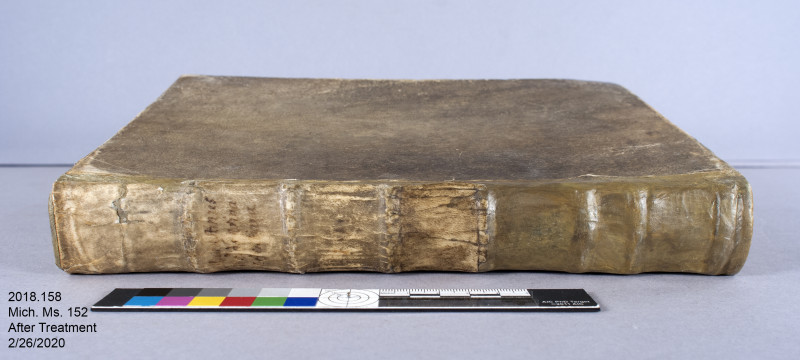

Lastly, the original vellum spine piece and the lifted vellum on the covers are re-adhered using wheat starch paste. The exposed Moriki layer is in-painted with acrylics and consolidated with a microcrystalline wax mixture to blend the new repair materials with the original vellum. In brief, the re-back using a Honey Hollow protects the damaged original spine material from tension when the book is opened.

The re-back using a Honey Hollow protects the damaged original spine material from tension

The physicality of touching history, of seeing original mends sewn into the vellum pages and covers, and studying the ink left by a steady, devout hand from centuries ago, are some of the elements that make viewing manuscripts firsthand so special and unique. Being able to repair this manuscript so that it is easier and safer to use, while learning a new treatment technique, is a great pleasure. Hopefully seeing a bit of the behind-the-scenes work that goes into making these collections accessible to faculty, students, and researchers will inspire you to seek out more treasures in the SCRC.

Now when the book is opened, a natural “hollow” forms due to the molded paper spine-former

Mich. Ms. 152, upper and lower covers, after treatment

Brooke Adams