A day like today, on April 22, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra died in Madrid four hundred years ago. To commemorate this date, I have revisited our collection of early editions of Cervantes's works, selecting for this post the eighteenth-century edition of Don Quixote that played a major role to canonize Cervantes as a global literary figure.

In 1738, the brothers Jacob and Richard Tonson published in London, with the support of Lord John Carteret, the first deluxe edition of the novel: a four-volume set in large quarto and richly illustrated with 69 copperplate engravings. John Vanderbank designed 67 of these plates; William Hogarth was responsible for a single one; and the portrait of Cervantes was drawn by William Kent. The engravers were G. Vanderguteh, B. Baron, and Claude de Bosc.

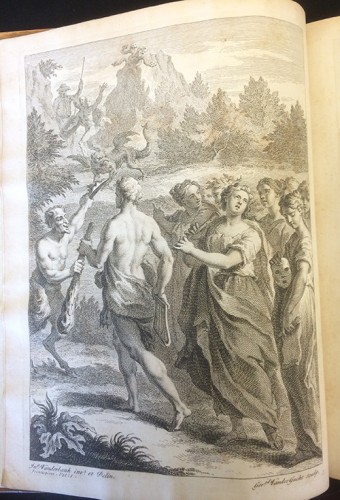

Frontispiece. Miguel de Cervantes. Vida y hechos del ingenioso don Quixote de la Mancha (Londres: J. y R. Tonson, 1738)

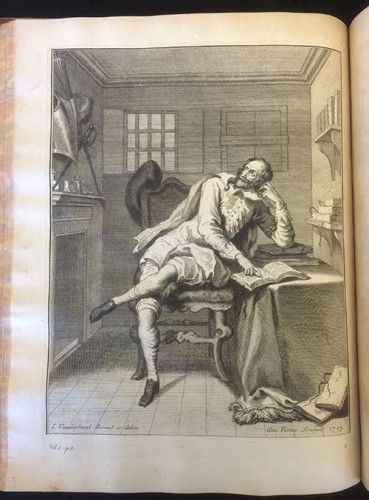

Formerly, the novel had been modestly published, reflecting the manner in which the text was expected to be interpreted: Don Quixote was just a series of grotesque episodes for the entertainment of the masses. But this 1738 edition would change everything. It was conceived not only to depict Cervantes as a respected author but also to read the novel in a certain way. It included the first portrait of the author, a biography of Cervantes by the scholar from Valencia Gregorio Mayans y Siscar and, more importantly, numerous illustrations that minimized what eighteenth-century intellectuals believed were the grotesque and excessive elements of the novel. Guided by the theory of decorum as summarized in the famous hexameter of Horace's Ars Poetica, "let each style keep the becoming place allotted it," some enlightened readers proposed that a character of the nobility and sophistication of Don Quixote could not be graphically humiliated by explicit representations of his pathetic adventures. Moreover, Don Quixote also embodied the eventual triumph of a serious prose against the insane frivolity of many novels of chivalry. For instance, the meaning of the allegorical frontispiece displayed above was carefully explained through John Oldfield's essay to the reader included in the first volume: Advertencias. In brief, Oldfield argues that Cervantes is represented by the mythological figure of Hercules Musagetes, the avenger of the Muses. A satyr, continues Oldfield, offers the Herculean Cervantes a mask, which symbolizes the playful tool of satire, and a club. With these weapons our author will be able to battle the monsters generated by the chivalry novels, the ultimate purpose of this struggle being to retore peace and equilibrium in Mount Parnassus, the home of the Muses. And the rest of the engravings consistently presents us Don Quixote himself as a humanized, even delicate, figure from whom we can learn as opposed to be the mere recipient of jokes and beatings.

Life of Cervantes by Gregorio Mayans y Siscar. Miguel de Cervantes. Vida y hechos del ingenioso don Quixote de la Mancha (Londres: J. y R. Tonson, 1738)

Beginning of the novel. Miguel de Cervantes. Vida y hechos del ingenioso don Quixote de la Mancha (Londres: J. y R. Tonson, 1738)

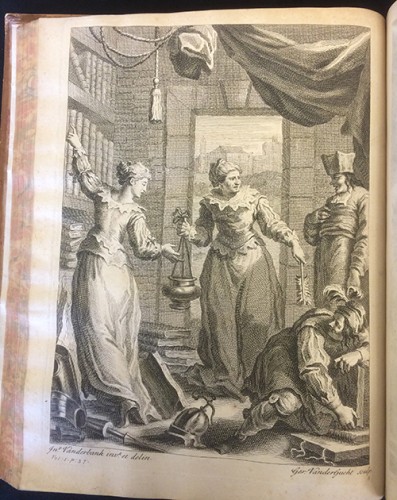

Don Quixote in his studio. Copperplate engraving. Miguel de Cervantes. Vida y hechos del ingenioso don Quixote de la Mancha (Londres: J. y R. Tonson, 1738)

In search of the chivalry novels to be destroyed. Copperplate engraving. Miguel de Cervantes. Vida y hechos del ingenioso don Quixote de la Mancha (Londres: J. y R. Tonson, 1738)

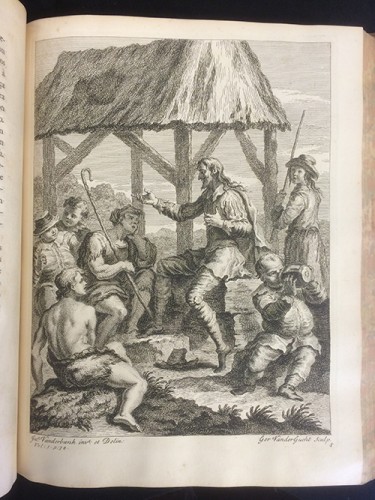

Don Quixote delivers his famous speech on the classical topos of the Golden Age (la Edad de Oro). Copperplate engraving. Miguel de Cervantes. Vida y hechos del ingenioso don Quixote de la Mancha (Londres: J. y R. Tonson, 1738)